Hi there,

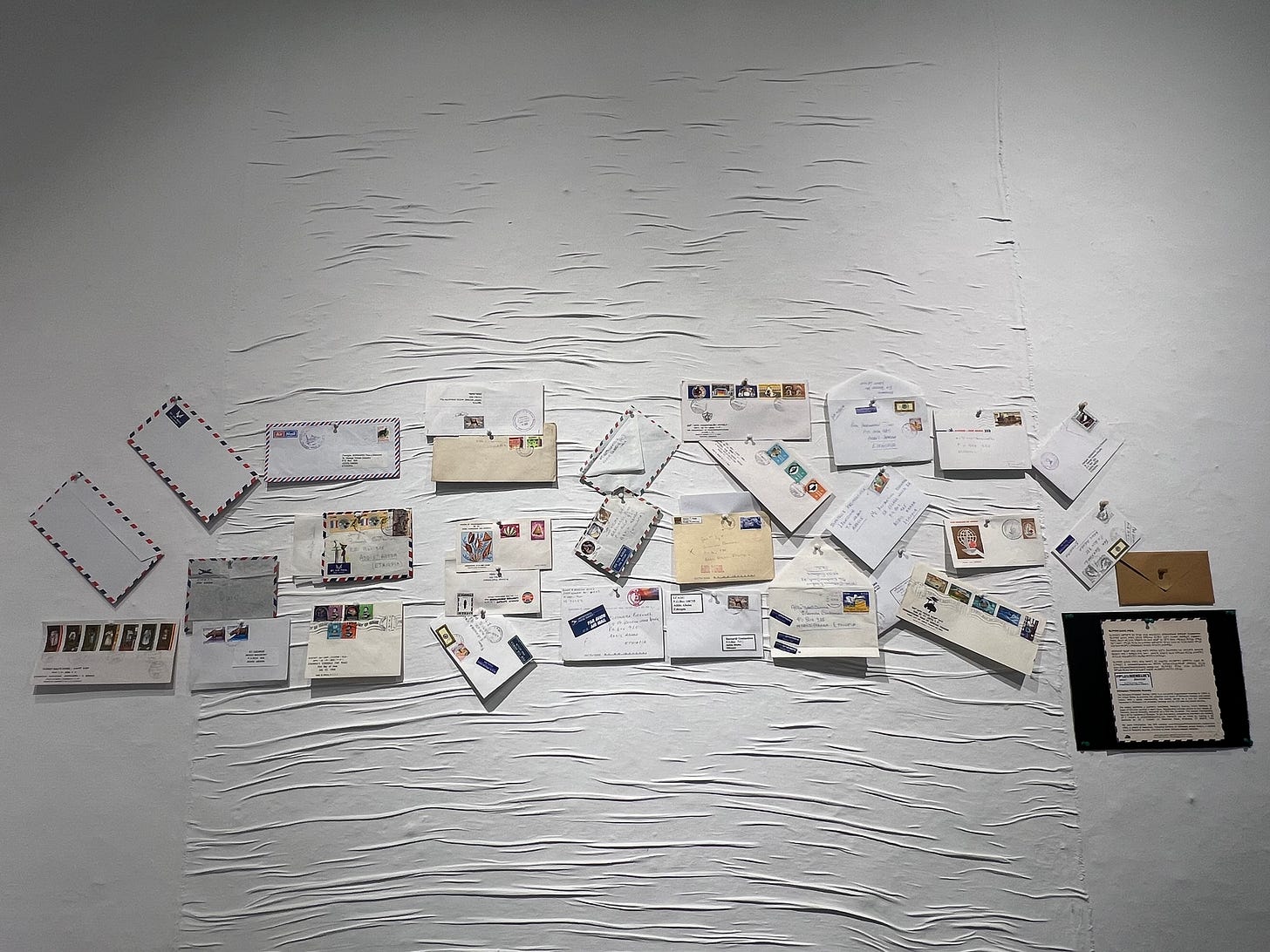

If you’re in Addis, I highly suggest visiting Yimtubezina Museum and Cultural Center inside Friendship Park (2). The museum has an open exhibition of stamp collections and first-day-issue envelopes that date back to the 1960s.

The collection includes stamps issued for different occasions (like the 60th anniversary of the ‘great October socialist revolution’) and themes, like hair, and clothing styles, of different ethnic groups in Ethiopia.

The museum used to be the home of a lady named Yimtubezinash (Habte) and is one of the few registered heritage sites in the city named after a woman. You can check out their Instagram page here, and see this collection before they wrap up.

To new subscribers, welcome!

My name is Maya Misikir, and I’m a freelance reporter based in Addis Abeba. I write Sifter, this newsletter where I send out the week’s top 5 stories on human rights and news in Ethiopia.

Now, to the news.

Media: women’s right...an afterthought

The Ethiopian Human Rights Commission, which recently got a new controversial Commissioner, released its latest research report focused on the Ethiopian media ecosystem.

The question posed in that research: what kind of (legal) regulatory frameworks are in place to protect the rights of women within the media and what does their implementation look like?

The research, which looked at 8 TV and 7 Radio stations in Addis Abeba, was initiated based on the complaints the Commission was getting: widespread violations of women’s rights happening in media (including unethical interviews on TV with women who had survived GBV, including rape – victim blaming, and normalizing violence).

While there are studies on how women are portrayed in media and ones on the roles they have in media houses, this one was intended to see if responsible bodies for regulation were doing their job (spoiler, they weren’t).

It classified the regulatory mechanisms from three perspectives: the government regulatory body, the Ethiopian Media Authority, the self-regulatory body, the Ethiopian Media Council, and finally, the media houses.

The Ethiopian Media Authority is the institution with the legal mandate to issue, renew, suspend, and revoke licenses to broadcasters in the country. Though part of the criteria for exercising this mandate is assessing whether broadcasters produce content that gives special attention to groups like women, the research found that there are no set standards to evaluate whether broadcasters comply. The interpretation of this assessment depends on who is in charge of the institution.

Overall, the research found that the Authority takes measures not based on a regular assessment, but on a case-by-case basis like when some egregious behavior goes viral on social media (remember the debacle with Abbay TV).

What about the Ethiopian Media Council, the self-governing entity made of publishers, broadcasters, and media associations? What regulatory framework do they have for ensuring women’s rights in the Ethiopian media ecosystem? Not much, says the report. The Council, established in 2019, has a monitoring unit but it is not yet functional. The ombudsman, set up by the Council, has not received any complaints yet, on rights violations against women in media.

The media houses are not much better. Most were unwilling to share their editorial policies with the Commission (pleading privacy reasons) and none have an in-house gender policy. One in particular, the privately-owned Ethiopian Broadcasting Service (EBS TV) was not cooperative at all, remaining unresponsive to all of the Commission’s inquiries.

The Commission has the legal mandate to launch investigations into human rights violations and others have the legal duty to cooperate in this process. It seems that EBS – which the Commission says has received a lot of complaints on how the channel portrays women, how its women staff are treated, and the content of their production, overall – has made the most of the gap in the accountability mechanisms. They know consequences are few and far between.

Of the 271 people in leadership positions across the 15 media houses surveyed, only 33 were women. Some media house representatives said they ‘don’t believe in affirmative action’ during the interviews.

None of the media houses included in this research reported getting any complaints on women's rights violations internally.

The full report, in Amharic, here.

Online safety: it’s worse over at TikTok and YouTube

In May last year, a study done across three major social media platforms - Facebook, Telegram, and X - showed that women in Ethiopia are facing serious hate speech online. The findings revealed that online violence against women is so common, that we can’t even clock it when it happens anymore; it is ‘normalized to the point of invisibility.’

The research was done in three local languages (Amharic, Afan Oromo, and Tigrignia) and English and resulted in ‘the most comprehensive inflammatory word lexicon in Ethiopia’.

The same researchers behind this, the Center for Information Resilience, have now shared highlights on what they found across TikTok and YouTube: ‘There is no platform that feels safe for women in Ethiopia.’

Gender-based violence is ‘an age-old problem’ yet this now happens at a much faster and bigger scale facilitated through technology. A prime example is my sister, who was forced to leave the country due to threats against her life, within days of a concerted online smear campaign. She is one of many Ethiopian women at the receiving end of online hate speech.

The research solves a big issue when it comes to what is broadly called, Technology-Faciliated Gender-Based Violence: in the past women’s experiences were seen as isolated incidents with ‘no data’ to back it up.

What the researchers have looked at in terms of hate speech is what is strictly considered as protected characteristics under Ethiopian law (the Hate Speech and Disinformation Prevention and Suppression Proclamation), which are: ethnicity, religion, nationality, sex, or disability. Anything that falls outside, cannot be categorized as hate speech, nor are there any legal consequences for perpetrators (even on paper).

The research points out that there is a difference in the hate speech that men and women experience on these two platforms: women tend to get comments that sexualize them, ridicule them (women’s sports as an example), and those that reflect gendered societal norms in the country.

Men on the other hand, get comments that challenge their masculinity (being called weak), and the abuse that is directed at them also ends up objectifying women (insulting their mothers – ‘raised by a single mother’).

The online hate speech against women also has an intersectional element. The researchers classified five other prominent identities they found along this gendered hate speech: Oromo, Amhara, Tigrayan, Muslim, and Other. Women with these identities received hate speech on both accounts.

The full research will be released soon, and I’ll share it here when it’s out. The link to the earlier research on Facebook, Telegram, and X, here.

Civic space: picking up speed

In October last year, a prominent human rights organization, the Center for the Advancement of Rights and Democracy (CARD), flagged its concern: ‘Political intolerance and economic instability are making it increasingly difficult for organizations to advocate for human rights and civic engagement’. Since 2020, 54 human rights defenders have been forced into exile, it reported.

By November, CARD and two other human rights organizations - the Association for Human Rights in Ethiopia, and Lawyers for Human Rights - had been suspended by the government regulatory body. By December, this number had increased to include two other organizations; the Ethiopian Human Rights Defender’s Center and the Ethiopian Human Rights Council. These suspensions are under further investigation and could lead to a decision to permanently shutter these organizations.

The regulatory body is now planning to revise its establishing law governing civil society (Organizations of Civil Societies Proclamation); one of the many laws that comprised the legal reforms that came after Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed took office.

One of the proposed changes to this law is the composition of the regulatory body’s board, which has 11 people. More specifically, the board has three representatives from the government, three civil society organizations, one expert, two members from the National Federation of Disability Associations, and two from women and youth associations.

What is the role of this board? To hear and pass final administrative decisions on appeals against decisions made by the regulatory body (on suspension of licenses for example).

The story, on Ethiopia Insider, in Amharic, here.

Funding: USAID cuts across sectors

The Trump administration's executive order to pause all foreign aid programs will have far-reaching serious consequences in Ethiopia. USAID is the largest bilateral donor of humanitarian assistance to Ethiopia.

Here’s an excerpt from a story on Addis Standard:

USAID’s Ethiopia portfolio is among the largest in Africa, second only to Egypt. In 2023, the agency provided over $897 million in humanitarian aid to Ethiopia, addressing conflict, climate shocks, and food insecurity. In March 2023, it announced an additional $331 million in assistance, bringing the year’s total to over $1.2 billion.

USAID’s engagement in Ethiopia spans 22 sectors, funding more than 357 projects— managed independently or in collaboration with 131 international and local partners working across the nation.

Last week, the Ethiopian Ministry of Health, said it had ‘instructed health bureaus to halt all activities and payments related to employees hired under U.S. government budget support’, according to Addis Standard. This will affect, ‘Addis Abeba City Administration Health Bureau and regional health bureaus in Amhara, Oromia, Tigray, and other regions.’

The Ethiopian Civil Society Organizations Council, which represents over 5,300 members, has also warned that ‘thousands of civil society employees could lose their jobs.’

Additionally, this will affect Ethiopia’s national HIV response, of which there are, ‘more than 270,000 beneficiaries across the Oromia and Gambella regions, as well as Addis Abeba.’

The full story on Addis Standard, in English, here and here.

Urban infrastructure: another community in jeopardy

I have written about the Corridor Development Project, the plan to transform Addis Abeba, ‘from a ramshackle city to a modern, hi-tech hub for foreign tourists and investors’ as put by a story in The Guardian.

The latest update I did, looked through a paper that explained Ethiopia’s political dynamics through its latest urban megaprojects. You can read that here.

Yet another tight-knit community will likely unravel because of this project: Club des Cheminots, a pétanque club at the Railway Workers’ Club.

Who are the members of Club des Cheminots?

Here’s an excerpt:

The majority of the club’s 150 members are pensioners who worked on the [French-built Ethio-Djibouti Railway] line and learned French after being sent to classes at Addis Ababa’s Lycée Guebre-Mariam. The line’s French workers popularised pétanque, also known as boules, by teaching it to their Ethiopian colleagues more than 100 years ago.

Why are they in fear that this might happen? Because the club’s location is ‘on a prime patch of land, a stone’s throw from Addis Ababa’s main square.’

The full story, which looks into why this community is important for its members, on The Guardian, here.

That’s all for this week. I’ll be back next week with more updates!

In the meantime, feel free to share this with anyone you think can benefit from keeping up with what’s going on in Ethiopia.

Was this forwarded to you by someone? Then hit the button below to subscribe and get free weekly updates.